7 Plots In Literature

Many academics, most notably author Christopher Booker, believe that there are only seven basic plot structures in all of storytelling – frameworks that are recycled again and again in fiction but populated by different settings, characters, and conflicts.

Those seven plots are:

- Overcoming the Monster

- Rags to Riches

- The Quest

- Voyage and Return

- Rebirth

- Comedy

- Tragedy

This list comes from Booker’s seminal book, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. It took him 34 years of research and reading to complete the 700-page psychoanalytic tome.

Posted by: The kidCourses Crew In 2004, Christopher Booker published The Seven Basic Plots—Why We Tell Stories, an iconic book that was 34 years in the making. In it, Booker identifies seven common story lines that he believes encompass the plots of virtually all of the stories ever written. According to different sources, there are only seven (or six, five, 20, 36 or three or one) basic plots (or themes) in all of literature. Parallel & nonlinear plots build suspense, leave the reader guessing, & show different perspectives. Learn more about plot structure & find student activities to explore narratives.

But where did the idea of a limited number of stories come from? Is it true? If so, how does that affect writers – all of whom strive to create their own unique stories?

Let’s dig a little deeper into this idea.

Although The Seven Basic Plots is the most frequently cited text today, Booker was not the first person to propose that there are a limited number of stories.

A list made by Foster-Harris in 1959 claimed there are only three stories:

Booker lists the 7 basic plots as: 1. Overcoming the Monster 2. Rags to Riches 3. Voyage and Return 5. James Payne, London, UK. Add your answer. Prezi’s Big Ideas 2021: Expert advice for the new year; Dec. How to increase brand awareness through consistency; Dec.

- Happy ending

- Unhappy ending

- Tragedy

While you can place every story you can think of into one of these three groups, it’s overly simplistic, offering little in the way of observation of actual story structure.

More recently (and perhaps intriguingly) the University of Vermont took a leaf from one of author Kurt Vonnegut’s theories and used powerful computer programmes to analyze 1,737 fiction stories. The purpose was to track the emotional content by looking for words such as ‘tears,’ ‘laughed,’ ‘enemy,’ ‘poison’ and so on. They describe building happy emotions as rise, and sadder emotions as fall.

Their results concluded that there were six basic master plots:

- “Rags to riches” (rise).

- “Tragedy,” or “Riches to rags” (fall).

- “Man in a hole” (fall–rise).

- “Icarus” (rise–fall).

- “Cinderella” (rise–fall–rise).

- “Oedipus” (fall–rise–fall).

The entire research paper isavailable to read online, but it’s heavy going. Rather wonderful, however, are the emotion graphs produced to track the patterns of happiness during the story arc.

Here, for example, we see the analyzed emotional arc of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling:

Dubbed the Hedonometer, the results of this analysis for a wide variety of novels isalso free to view online, and makes for a fascinating resource for writers who like to analyze books in detail. Of course, not every book in the world has been analyzed, but most of the classics and popular books are there for you to peruse.

(It’s also worth bearing in mind that this most recent analysis only looked at fiction available on Guttenberg – mostly older classics and all in English. Deeper exploration of other cultures and recent ideas might uncover wholly new stories.)

Ultimately, what does all this science mean? If every story has already been written, is striving for originality a pointless task?

The answer is no; it absolutely is not. While it may indeed be compelling – and likely true – that storytelling conventions are built on only six or seven broader foundations, the purpose of categorizing stories into broad types is as a way to understand fiction, not to limit our creativity.

These frameworks describe the emotional journey at the core of each story, but they can never define the limitless, majestic scope of the sights, sounds, people, and places readers can encounter during that journey.

While films such as Apollo 13 and Mad Max: Fury Road, and books The Hobbit and Alice in Wonderland are all in the “Voyage and Return” category, they’re still worlds apart in their content – uniquely positioned for very different audiences.

Stories stand on their own because of the people that write them, and the characters they create.

So remember: even if there are only seven stories – or three or six, or whatever researchers suggest next – it doesn’t mean you don’t have a worthwhile story to tell. From a framework perspective, it may all have been done before – but only the most cynical could use that as a reason not to write.

But with all of that said, how can we gather some useful information from these studies? Well, you could do worse than checking out some of the Hedonometer graphs for books that have inspired your work. If something in your early drafts seems to be missing – like the story just isn’t pulling you in like you’d hoped it would – try comparing it with the emotional journey laid out in those graphs. How are you engaging the reader on an emotional level with your language in comparison to these other works?

20 Types Of Plots

A few tweaks here and there to bring your story more closely in line with the framework readers expect may just make the psychological link you’re looking for.

On the other hand, you might choose to follow your own inspiration and strive for more peculiar greatness. It’s all up to you.

Adding an eighth storytelling wonder to the world doesn’t sound like too bad a prospect, does it?

What do you think? Do you agree with the theories surrounding possible story arcs? Which do you find to be the most appealing as both a reader and a writer? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Example Questions That Can Be Answered Using This FAQ

- I’ve heard there are only 7 (or 5, 20, 36…) basic plots (or themes) in all of literature. What are they?

People often say that there are only a certain number of basic plots in all of literature, and that any story is really just a variation on these plots. Depending on how detailed they want to make a 'basic' plot, different writers have offered a variety of solutions. Here are some of the ones we’ve found:

1 Plot 3 Plots 7 Plots 20 Plots 36 Plots

1 Plot:

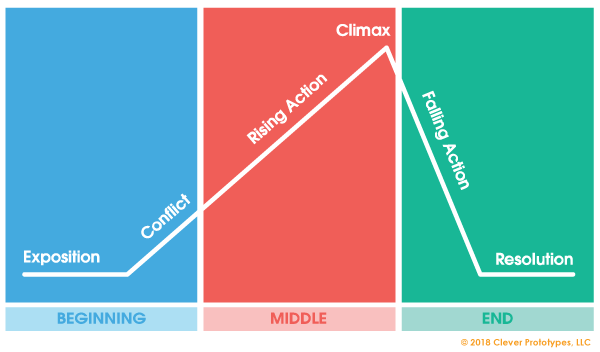

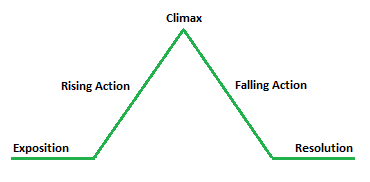

Attempts to find the number of basic plots in literature cannot be resolved any more tightly than to describe a single basic plot. Foster-Harris claims that all plots stem from conflict. He describes this in terms of what the main character feels: 'I have an inner conflict of emotions, feelings…. What, in any case, can I do to resolve the inner problems?' (p. 30-31) This is in accord with the canonical view that the basic elements of plot revolve around a problem dealt with in sequence: 'Exposition – Rising Action – Climax – Falling Action – Denouement'. (Such description of plot can be found in many places, including: Holman, C. Hugh and William Harmon. A Handbook to Literature. 6th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co, 1992.) Foster-Harris’ main argument is for 3 Plots (which are contained within this one), described below.

3 Plots:

Foster-Harris. The Basic Patterns of Plot. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959. Foster-Harris contends that there are three basic patterns of plot (p. 66):

- '’Type A, happy ending’'; Foster-Harris argues that the 'Type A' pattern results when the central character (which he calls the 'I-nitial' character) makes a sacrifice (a decision that seems logically 'wrong') for the sake of another.

- '’Type B, unhappy ending’'; this pattern follows when the 'I-nitial' character does what seems logically 'right' and thus fails to make the needed sacrifice.

- '’Type C,’ the literary plot, in which, no matter whether we start from the happy or the unhappy fork, proceeding backwards we arrive inevitably at the question, where we stop to wail.' This pattern requires more explanation (Foster-Harris devotes a chapter to the literary plot.) In short, the 'literary plot' is one that does not hinge upon decision, but fate; in it, the critical event takes place at the beginning of the story rather than the end. What follows from that event is inevitable, often tragedy. (This in fact coincides with the classical Greek notion of tragedy, which is that such events are fated and inexorable.)

7 Plots

7 basic plots as remembered from second grade by IPL volunteer librarian Jessamyn West:

- [wo]man vs. nature

- [wo]man vs. [wo]man

- [wo]man vs. the environment

- [wo]man vs. machines/technology

- [wo]man vs. the supernatural

- [wo]man vs. self

- [wo]man vs. god/religion

7 Basic Plots

20 Plots:

7 Plots In Literature

Tobias, Ronald B. 20 Master Plots. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1993. (ISBN 0-89879-595-8)

This book proposes twenty basic plots:

- Quest

- Adventure

- Pursuit

- Rescue

- Escape

- Revenge

- The Riddle

- Rivalry

- Underdog

- Temptation

- Metamorphosis

- Transformation

- Maturation

- Love

- Forbidden Love

- Sacrifice

- Discovery

- Wretched Excess

- Ascension

- Descension.

36 Plots

Polti, Georges. The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations. trans. Lucille Ray.

Basic Story Plots

Polti claims to be trying to reconstruct the 36 plots that Goethe alleges someone named [Carlo] Gozzi came up with. (In the following list, the words in parentheses are our annotations to try to explain some of the less helpful titles.):

What Is The Plot Of A Story

- Supplication (in which the Supplicant must beg something from Power in authority)

- Deliverance

- Crime Pursued by Vengeance

- Vengeance taken for kindred upon kindred

- Pursuit

- Disaster

- Falling Prey to Cruelty of Misfortune

- Revolt

- Daring Enterprise

- Abduction

- The Enigma (temptation or a riddle)

- Obtaining

- Enmity of Kinsmen

- Rivalry of Kinsmen

- Murderous Adultery

- Madness

- Fatal Imprudence

- Involuntary Crimes of Love (example: discovery that one has married one’s mother, sister, etc.)

- Slaying of a Kinsman Unrecognized

- Self-Sacrificing for an Ideal

- Self-Sacrifice for Kindred

- All Sacrificed for Passion

- Necessity of Sacrificing Loved Ones

- Rivalry of Superior and Inferior

- Adultery

- Crimes of Love

- Discovery of the Dishonor of a Loved One

- Obstacles to Love

- An Enemy Loved

- Ambition

- Conflict with a God

- Mistaken Jealousy

- Erroneous Judgement

- Remorse

- Recovery of a Lost One

- Loss of Loved Ones.